Lock before Key

2020 September 30th

Lock before Key

One of my favourite game design mantras is Lock before Key. Succinct and sweet, it summarizes an important game design principle that makes problem-solving more rewarding.

In game design, locks and keys have been a prevailing choice for guiding the player and defining pacing. However, designers are only partially able to choose how the player moves through and experiences their game. A locked door slows the player down while they find a key to continue progressing.

These interactions can and should be crafted to make this "slowing down" rewarding. When the player is challenged with a locked door, they will want to open it. When they discover the key, not only do they progress in the game, but they have solved this internal puzzle for themselves. This order is important because a key without a lock is useless. A random key is not a problem for your player to solve.

Beyond the Lock

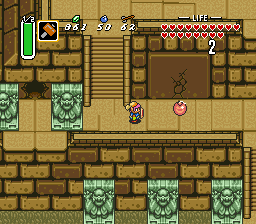

I first heard the phrase on the Lostcast podcast, but it originates from an analysis of how Zelda gets lock and key puzzles right.

Locks can take many forms: impassable rivers, high cliffs, invulnerable monsters. Keys also: rafts, jumping boots, flaming swords. Provide the need before the solution.

- Matt Hackett from Lostcast

Lock before Key compresses this complex idea. Showing the problem first is what makes the entire interaction challenging and rewarding. A player armed with the solution skips any mental processing and curiosity. Instead, they continue to breeze through the game without another thought to the problem. Scenarios designed problem-first build engagement throughout the solution process while leading to the same conclusion. Taking this approach and generalizing "the lock" to "a problem" makes this concept more extensible.

Metroidvanias take this idea to the next level. Levels are often a convoluted maze of rooms and enemies. The player explores and uncovers new abilities and items as they continue. These discoveries allow them to jump higher, break walls, or attack in a new way. Now the player must backtrack to earlier parts of the map. The player is able to overcome previous roadblocks with these game mechanics acting as the keys. Jump wide chasms, destroy cracked walls, and defeat impossible bosses. Although the map is vast and confusing, the interconnected nature of the game mechanics gives the game direction.

Meaningful Challenge

Challenge takes on a significant role in shaping the player's experience. Although I have dissected the "failure" side of challenge in a previous blog post, I want to focus instead on motivation. Locks, are an opportunity for the player to self-motivate. The unknown of a locked chest will be a drive for the player.

Designing meaningful problems comes down to two things: memorability and pacing. Feel free to hide these problems in plain sight, but make sure the player will remember them. If the player's curiosity is piqued by the lock, this will entrench the motivation and satisfaction. Similarly, overloading the user with many problems will detract from their self-motivation. Instead, problems are most engaging when adequately spaced out.

Some games use difficulty as their lock. Teaching the player how to perform a wall-jump may be the key they need to progress against an earlier barrier. Serious skill-based games take this one step further. By increasing the difficulty as the game continues, the player's own experience acts as the key to new and exciting challenges. Only players who have been taught to (given the key) triple wall-jump can even reach this next challenge.

Don't give away the fun

Recently, a friend was telling me about rock climbing. Solving a climbing problem is partially the physical scaling of the rocks and partially the mental puzzle of determining a route that the climber can accomplish. This puzzle is called beta (jargon used to describe information about how to climb a route). Determining your beta is a major part of rock climbing fun. As such, unwanted sharing of beta (or advice) is a huge faux pas. So much so that they have the term spraying beta to denote it.

Don't spray beta. Don't give the player the solution before they even think about the problem. Put the lock before the key.

Thank you for reading. Thank you for exploring ideas with me.